How to improve speech intelligibility when amplifying the voice

When listening to an amplification or a recording of a person speaking, the ability to understand what is being said – or sung – depends on several factors, such as the quality of the recording including the microphones, the playback system, the acoustics of the room, background noise and much more.

When voice is amplified or recorded and then later played back, there is a risk that some essential information in the audio is lost along the way, Fortunately, with a few helpful tips and some understanding of that factors that comprise speech intelligibility, we can minimize this risk, ensuring clean, understandable audio.

This article will touch on a few elements that have a bad influence on speech intelligibility and give some solutions to the problems that can occur.

Placement

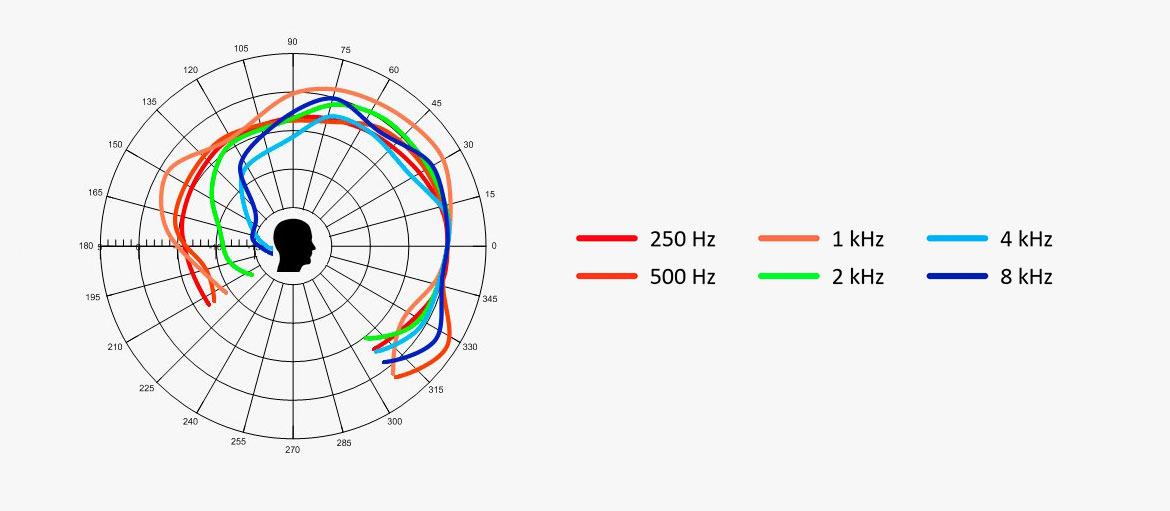

The voice is commonly picked up in front of the person speaking. When you have a private conversation with someone, you would be placed 1 meter in front of the person. This is considered “normal” distance and is perceived as normal speech sound. Moving below or behind the speaker, changes the sound, and compromises intelligibility. Listening behind the person talking is not ideal, but even positions below the mouth, like on the chest, will introduce some intelligibility challenges. This is because the frequency range between 2 to 4 kHz, where the important consonants are predominant, is suppressed in this position on the chest. This sound is often perceived as if it was generated from the chest. This is NOT the case. The phenomenon “chest sound” is acoustical due to body absorption and head shape. The sound is generated from the vocal cords and the level of this sound is louder than the sound generated from the (small) vibrations from the chest.

The figure below shows the frequencies of the voice above and below the mouth where the horizontal axis 0° is normalized, the reference point.

(ref.: Chu, W.T.; Warnock, A.A.C.: Detailed Directivity of Sound Fields Around Human Talkers.)

Consonants and vowels

Language consists of both consonants and vowels. Consonants are higher frequencies while vowels are represented at lower frequencies. Vowels are soft rounded sounds and consonants are mostly hard sounding, but this differs from language to language. For example, the consonant W does not sound hard in English. This article will focus on hard-sounding consonants like F-K-T-S.

When we raise our voices, we add energy and level to the entire word. We are not able to add much level or energy to the consonants, but we can easily add energy to the vowels. If you yell the sound of the letter T, you raise the level of the vowel E in the word TEE. Try it. Just yell [T]…. not much level. Now whisper the sound [T]. Easily done. Yell the sound of the vowel A. Easy to hear and understand but if you whisper this vowel sound, you lose meaning.

By raising our voices to become more intelligible, the level differences between the weaker consonants and the louder vowels, increases and eventually ruins speech intelligibility. The consonants become masked, or drowned, behind the vowels. When we whisper, the opposite happens; the vowels drown. To maximize intelligibility, keep your voice at a normal speaking level.

Echo or reverb (room acoustics)

Another factor that can ruin speech intelligibility is echo or reverb. Echoing sounds appear when the sound is being repeated one or more times as reflections of the original sound on hard surfaces. If you speak or aim a loudspeaker into a hard, reflective surface, the sound will be reflected to you. If there are many reflective surfaces, the repetitions will be heard as reverb, which will eventually ruin speech intelligibility. A little reverb can be nice for musical vocals but is rarely good for speech where the message is more important than nice sound. In some cases, the reverb is so loud that the accumulating reflections are drowning the direct sound from the speaker. A large cathedral with many hard surfaces and little to no absorption often has a lot of reverb, which ruins speech intelligibility. The sound will be heard as an echo if the time between the repetitions is longer than 50 ms (~ 17 meters).

Distortion

If sound is being amplified or recorded and played back, the same considerations should be made but, in this situation, there are even more risks of ruining speech intelligibility.

Distortion is unfortunately quite common. If you have never had the possibility to hear the same audio chain in an undistorted system, it can be hard to hear the distortion and what is ruining the sound. Distortion appears if any link in the audio chain is incapable of handling the level of the audio peaks that the voice produces. The distortion can be caused by inferior quality equipment or equipment that is not set up correctly.

The voice can be very loud and can be very soft. To handle both ends of the level spectrum, you need audio systems that can handle sounds from a whisper all the way up to a loud yelling or even screaming.

Level settings gain structure of the audio chain, sound pressure level [SPL] handling and the sensitivities of the microphones used, are some of the key elements that you need to consider when working with the human voice.

Background noise (acoustic)

Unwanted background sounds, including music, can ruin speech intelligibility. If there are other sound sources in the room or in the recording, chances are that these sound sources take up space in the audible spectrum, that was meant for the voice. Imagine the person you wish to hear, is standing next to roaring train passing by. The background sound is louder than the speech. A less extreme example could be the sound of the ventilation fan in your computer or the typing of the keyboard when you are taking part in an online meeting. These sounds can disturb the meeting, reducing the ability to hear what you or others are saying.

There are more factors that can influence speech intelligibility, but those mentioned in this article are the most common and easiest to correct.

Solutions

Consonants vs. vowels:

- Balance the consonants with the vowels – do not yell!

- Add pauses. Speak slowly. Give the consonants time and space

Echo, reverb (room acoustics)

- Add absorption to avoid reflections

- Angle reflective surfaces so that reflections do not bounce directly back to the source they came from

Distortion (electric)

- Choose a microphone that can handle both soft and loud voices

- Monitor the gain settings on your microphone input stage – mixer or wireless system

Background noise (acoustics)

- Close windows

- Turn off fans that create audible noise or wind into the microphone

- Choose a microphone that can be placed close to the mouth, like a headset or podium microphone